Vermeer in Details

Very little is known about his life. He lived in Delft, the son of a silk tradesman, and in 1653 he married Catharina Bolenes, who came from a wealthy Catholic family, as opposed to his less well-off Calvinist family. It appears that Vermeer dedicated most of his life painting and to an extent, art dealing. He produced artworks at a slow pace and mostly took orders from his few local patrons; he was eclectic and spent copious amounts of time on an artwork. He died in depression in 1675 because of the dramatic deterioration of his financial condition. Vermeer was survived by his wife and eleven children, who inherited his debts. Catharina Bolenes had to sell his remaining paintings in order to satisfy his creditors, one of which appears to be her own mother.

Vermeer had a very distinct style with attention to detail in all the subjects that he painted, including portraits and cityscapes, as well as seduction scenes. His portrayal of the 17th century Dutch society had no limitations on the choice of the people depicted, ranging from a milkmaid to luxuriously dressed women accompanied by their maids. The intricate orchestration of his works brings to mind a photographer’s work; with his paintings, such as A Lady Writing (1665) he makes us feel as if we stepped into a moment of the everyday life of the person depicted, turning us into indiscreet, curious voyeurs. We can’t look away from his painting, yet we feel unnecessary and uninvited.

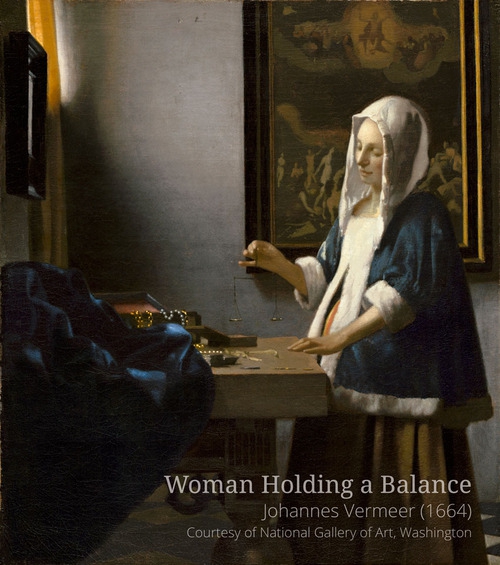

Woman Holding a Balance (1664) was executed like most of Vermeer’s paintings in his studio, recognised by the distinct furniture and items on the painting. The artist has depicted a young woman carefully holding a balance, which was initially thought to contain pearls or gold, but research showed that it is actually empty. The concentrated woman stands in front of a heavy oak table that has a jewellery box full of pearls, some silk ribbons and a dark blue cloth on it. The pale light that enters the room through the heavy curtains divides the space in two, the lighter upper left side and the dark lower side, where we can hardly make out the objects in the painting. However, the dark side is somewhat brightened because of the light reflected on the pearl jewellery, a pattern that emerges in many Vermeer paintings.

A painting of the Last Judgement is hung in the wall behind the woman, charging Vermeer’s painting with an eschatological message. Christ can be seen, with outstretched hands, separating Good from Evil, the Blessed from the Damned. The balancing of the scales by the woman is a direct reference to the weighing of the souls by God. However, we now know that the scales are empty. Could it be that the simple-dressed woman has decided to forgo her vanity and renounce her valuable possessions? Or could it be that Vermeer is making another kind of comment; one on the futility of the greediness of human nature?

What distinguished Vermeer among other painters of the Dutch Golden Age, was not only his distinct style, unique mannerism and tenderness with which he executed his paintings, but exactly his ability to convey moral messages from the depiction of quotidian life.

Alkistis Dimaki is an art professional with an MA from Goldsmith’s, University of London and a BA in Archaeology & History of Art. Alkistis is an administrator of arts & culture projects and a contributing author for USEUM.